|

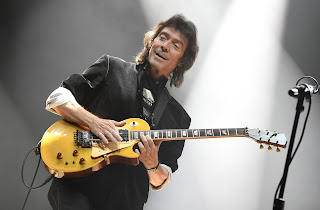

| Image by Lee Millward |

Sitting at my laptop preparing this

interview, I am thinking back to two years ago today, March 8, 2020, when Steve

Hackett and his band were appearing at the NYCB Theatre at Westbury. The

concert marked the last live event I would attend for quite some time, as well

as one of the final performances Hackett gave prior to the pandemic tightening

its grip on the globe. Fast forward through the Twilight Zone era to now …

after writing, recording, and releasing two terrific albums during 2020-2021, Hackett

is back on the road, bringing his Genesis Revisited: Seconds Out + More tour

across the world, arriving at the illustrious Beacon Theatre in New York City

on April 3.

|

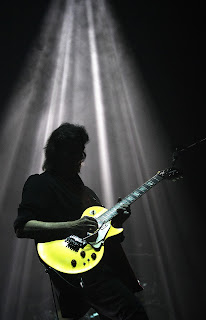

| Image by Christopher Simmons |

Having established a dialogue that

began in 2014,

continued in 2015

and again in 2020,

I have been unfailingly impressed by this soft-spoken, erudite artist whose

love for music, his wife Jo, and his legion of fans is evidenced by the degree

of honor he devotes to all. Hackett’s fans have become an extended family to

whom he affords the greatest respect an artist can offer; by staying in tune

with their musical hopes and dreams, he delivers the goods with a steadfast

consistency that acknowledges the fervent admiration bestowed on him and the

vast body of music he has been responsible for creating for more than 50 years.

And so it was, my phone rang promptly

at noon several days ago, and I answered to the now-familiar sound of Steve

Hackett’s voice. Read on for the rest of the conversation … and enjoy!

|

| Image by Lee Millward |

Roy Abrams: Hello!

Steve Hackett: Hello! Is that Roy?

RA: Yes, it is! This must be Steve—how are you?

SH: Yeah, very well, Roy, how you doing?

RA: I’m okay, and I’m hoping all is well with Jo as well?

SH: Yeah, all is good, all is very good, nice to talk to you,

mate.

RA: Thanks, same here! It’s been a while! You were the last artist

(my family and I) got to see in concert before everything hit the fan.

SH: My God, it was all going so well, or so we thought and then

suddenly the carpet got pulled, everything got closed down, and we got the last

flight back home from Philadelphia. We filled in the time without gigs with

loads of recording, but I’m back in the saddle now!

RA: Can’t wait to see you at the Beacon! On another note, I

want to congratulate you on the two magnificent albums you released last year.

SH: I’m glad you liked them! Yeah, I enjoyed doing both—I really

enjoyed doing the acoustic one just to sort of (recover) after all the recent

mishaps. I thought, hell, if I can’t do what I’m supposed to do, I may as well

do something that I enjoy doing. So, I did that kind of escapist album; the

main thrust of it was to do a virtual journey around the Mediterranean—Under a Mediterranean Sky. The other one, Surrender of Silence, has some aspects of

travelogue about it, maybe not so much, it was more of a kind of heavy metal

album, or melodic metal.

RA: Surrender of Silence could serve as a primer for the

initiate to your music, as it contains the quintessential blend of atmospheres

and textures that has always been a distinct hallmark of your creativity as a

guitarist, as a songwriter, and as an arranger/producer.

SH: Yeah, it’s hard, you know, to know. There have been times

where I’ve approached albums as a songwriter, other times I’ve approached

albums as a guitarist. I guess Surrender of Silence was a mixture of the

two. The first track we did was “Natalia.” I was very proud of

it, with all of the arrangements, and the orchestral stuff, and the kind of nod

to Prokofiev and Tchaikovsky, and the whole

cinematic thing, but I realized that it was a few minutes before you’ve got a

single note of guitar, so I redressed that by doing an intro that was all about

tapping, so in a way, they were twins, I think they were brother and sister,

really. (There were) certain things that had become cinematic throughout the album.

I had a blast doing it! I think it’s a very intense album. (When) people say

they like hearing it, I say, well, how did you manage to sit through it

from beginning to end, because you’re getting bludgeoned over the head all the

time. With the gentle stuff, I can understand, but I quite like being more

aggressive, I must admit.

RA: As you said, it’s a melodic metal-progressive touch that is

present. “The Devil’s Cathedral” is a personal

standout. The combination of instruments, the heavy atmospheres, the kind of

twist of dark humor that winds through the lyrics, along with the scene shifts

in the music all serve to evoke your earlier musical journey.

SH: I know what you mean. “The Devil’s Cathedral” is really Son of

Genesis, isn’t it? It’s got that aspect. But it goes to places that Genesis

wouldn’t have gone. You wouldn’t have had pipe organ with soprano sax playing

off each other. But it works really well live, believe me. That one is a

standout for me, live. I think it works better live, to be honest, than it does

on record—and it works well on record! But there’s something that

happens—letting the dogs out—let loose the hounds. That song, live, it just

seems to get sharper teeth, really.

RA: Perhaps more than any other artist who celebrates the music

from their earlier career, your approach is meticulously crafted, exquisitely

arranged, and presented to your fans in a way that demonstrates how you honor

their appreciation of your music. You’ve said in the past that you view your

fans as the “drivers’ of your music in terms of what you do in a live setting,

and I’m wondering what motivates you to take that path. What is your view of

artists who claim that the only way for them to continue to perform their

earlier material is to change it up so they don’t get bored. In your opinion,

is that a cop out, or is it a valid perspective?

SH: Well, you’ve raised a number of issues there. I think, to do

authentic versions, recognizable versions … to me, that’s important. Now, you

can be flexible with the instrumentation. I like to have brass and woodwinds

for an extended range, sonically, and at times when I’ve rerecorded any of this

stuff, I’ve gone all out occasionally. Put an orchestra or two on it! The same

sense applies when we’re doing it live. I don’t want to change it so much that

it’s unrecognizable but I do want to be able to be as free with it as I think

we were when we (Genesis) were doing it as a band originally. There might be a

solo or two that may change, but not necessarily. Some solos, like the one at

the end of “Supper’s Ready,” I feel once I’ve done

the established phrases, I can go off the map and do something else, improvise

and improve on it; take it to the mountains. With certain tracks, if I change

the solos, the song would not work anymore. Do you know what I mean? The guitar

solo at the end of “Musical Box,” I couldn’t really

change a note on that. It’s basically part of the song. When I was hired to

play with Genesis all those years ago, the idea was (that) to do a solo, you

write it, like classical music. That’s how I approached it. I tried to honor

it, but I don’t want to honor it to the point where, for instance, if a solo

that Rob might do on soprano sax on “Firth of Fifth,” I don’t want to feel

like I’ve got to say to him, okay, the original was done on flute, so you’ve

got to do it on flute. I don’t see it that way. We’re not a tribute band; we’re

playing music that is allowed to evolve. Sometimes when I do re-recordings, I

take (liberties) with it; certainly, the first Genesis Revisited, I changed the

arrangements greatly on some of (the tracks). On other things, I stick with

(the original arrangement) more, provided it’s a recognizable riff; I want to

please the audience—the audience that owns it; the audience that were the

midwives to its birth, if you know what I mean.

RA: Yes, I do. That’s a wonderful way to put it: the audience

who owns it.

SH: It’s not the writer’s, it’s not the performer’s, it’s the

audience that owns it because they know what it’s all about much more so than

those who once performed it, perhaps dismissed it, or in my case, went back to

an abandoned place and repopulated it.

|

| Image by Howard Rankin |

RA: Roger King seems to have become

your closest musical collaborator of those you’ve worked with to date. Is that

an accurate assessment? If so, what’s made the journey with this particular

person so fulfilling and this long-lasting?

SH: I’ll tell you what it is. I write with (my wife) Jo, I write

by myself, and I write with Roger. There are three possibilities, and sometimes

we do all that together. The thing about Roger is that he’s very hard to

impress. He’s nobody’s “yes man.” In a way, although I employ him, he will be

sufficiently critical and be able to say, “That doesn’t really work, we should

do this.” I don’t think he’s ever said to me, “You could do better than that,”

but I could tell with just a look. Nobody has the answers all the time, even

the greatest musical geniuses. Nobody really can do this on their own, is what

I’m saying. You need the input of others … all music ends up being

collaborative, it seems to me. He’s a great collaborator but there are times

when it’s frustrating; I know that he’s never actually impressed with anything.

The most he’ll say is, “I don’t mind that.’ He’s the master of understatement

and very British! He doesn’t jump for joy, but I can tell when he feels that

things are not too bad, and that’s the most you can expect from Roger. He’s not

a “Wowee!” kind of guy …

RA: I also wanted to touch on your collaboration with Jo, which I’ve watched

blossom over the last several years. How would you characterize the evolution

of that creative partnership?

SH: I wrote tons of lyrics before I worked with her. Originally,

we met when she wanted me for a film she was making. The thing (about) her

approach to songwriting is that she needs to know what the song is about. It

needs to have a theme; that might be just one word. For instance, “Natalia,” on

the album. She was the birth of that; she came up with the lyrics, first of

all, and then my input was to say, I think we can find a good name for this

person. We both liked the name Natalia, we felt that that worked, and then I

would work with her rough (draft) and try and be flexible with the meter. I

didn’t really know what to do with it, first of all. I thought, well, here’s a

challenge; I don’t know how the hell I could make this work. Once I got the

idea of Russian orchestration via the influence and inspiration from Prokofiev,

suddenly it all started to make sense; the idea of darkness and light, like a

scene from Romeo and Juliet, so that’s really what made that work. If

ever I do anything that would almost be casual, she’ll say to me, “You know,

you could do it with just a bit more importance here.” She says to me that she

would prefer heavy metal that is at least passionate, compared with all the

harmonic changes in the world if they’re just the equivalent of—I don’t know—"vacant

casual.”

RA: You’ve characterized your music as “film for the ear.” I’m

sure your fans would agree that the spectrum of images contained in these two

recent albums bears evidence to just that. On a personal note, having listened

to your music since my teens, I can tell you that I am invariably transported

by the experience,

SH: That’s the idea of it! It’s nice to pull that off; it’s great.

As I say, I work with a songwriting team where at least I feel—yes, I know I

could override everybody and use the power of veto, but I feel if it resonates

with my key collaborators, I could also collaborate with others once we’ve got

the heart of the song sorted, then we can take on the influence of others,

their performances, so they can flesh out the details. I know that Rob Townsend can sail through

practically anything the first time; he practically doesn’t need to hear

anything! He can hear the most complicated changes and play the most fluidly

exquisite solos over the top; he has extraordinary command of musical theory

combined with chops to die for! That works very well and similarly, with other

people I work with. There’s a lot of input from Christine Townsend as well on this album.

She doesn’t tour with us; although she shares (Rob’s) surname, they’re not

related. She plays great, wonderful viola and violin, and so I arrange

everything around her. She’s been working with us for quite a few years. It’s

the first time she ever wrote back and said, “I lived with the album for a bit

and I absolutely love it,” which is marvelous. I seem to be doing something

right. All I have to do is jump in headlong (or feet first) and then we’re in a

world where anything can happen. That’s the idea; keep it fast and loose.

RA: I read a recent interview where you said,

“There’s some tremendously talented people that I really wish I could just

phone up and say, ‘You might like this one.’ Things can often come so close.”

Was that an indirect reference to the time (2005) when you, Peter Gabriel, Tony

Banks, Mike Rutherford, and Phil Collins were planning on doing something

together but it fell apart, or was that a reference to some other artists?

SH: I don’t remember the exact quote, but I think my time with

Genesis (is over). I try to honor the music. (Band politics aside), I did like

the stuff we did together. Whether or not (a reunion) would be possible, I

don’t know. I guess everyone has been allowed to rule their own patch so much

that I don’t know whether that collaboration would be possible.

RA: Other than Genesis, who else is on your bucket list?

SH: Oh my God, it’s so very hard when I think about it. There are

times when I think to myself, I really ought to ask John McLaughlin if he would like to

play on something. I did enjoy his work so much, especially with Miles Davis and Mahavishnu Orchestra. I have no idea whether

he would be interested in doing something or not. I had hoped to work more with

Ian McDonald who sadly passed away

the other day and also not just him but Gary Brooker. He and I had been

talking recently and we were hoping to maybe do something. Unfortunately, the

pandemic just got in the way. I know that Gary and Ian had worked together on

Ian’s album Driver’s Eyes. To my mind, the

outstanding track is “Let There Be Light”—the combination of the

two, and also the magic writing team of McDonald and Pete Sinfield. I think that was a

terrific combination. They started to get something of the Crimsonite magic

there; the epic swell of that, the unlikely changes, and Gary’s soulful voice.

That didn’t happen for one reason or another but we’re talking about people who

are no longer with us yet somehow, in spirit, they seem to be stronger than

ever!

RA: For the past few years, David Crosby has been saying that

music is a lifting force to which he feels compelled to contribute as much as

he can for as long as he can. Has music’s role taken on an expanded meaning for

you personally during the past two years? Do you feel a similar sense of

urgency, given the passage of time, and given the dark times in which we now

find ourselves?

SH: Certainly, I would agree with all of that, the sense of

urgency to make sure all those brainchildren are born as quickly as possible,

still wanting to pay attention to detail, because the devil, of course, is in

the details. David Crosby is a very interesting character; I know he’s had his

demons himself, of course, nobody says he’s easy (to work with), but I think

he’s a good talent with an extraordinary voice. I think he’s very, very

important and helped to sculpt the music scene in not just the ‘60s but beyond

that. It was very interesting to see both Crosby and Nash with David

Gilmour. Very impressive that they happened to be on the title track of his album. Somehow, I think it’s

wonderful when you get a sense of bands coming together. I had a sense of that

when I was working with Chris Squire, where you take a pinch

of Genesis and add a teaspoon full of Yes and see what you get.

That’s what we did together. These collaborations are great when it’s people

(with whom) you’ve spent time in their company, shall we say, even though they

weren’t aware of that. Through the time (spent) listening to their music,

they’ve become part of your DNA. When you get to work with one of those every

now and again, it’s a real blast.

|

| Backstage with Steve Hackett March 8, 2020 NYCB Theatre at Westbury Image by Roy Abrams |

© Roy Abrams 2022